I wrote the following piece for the OCD-UK website during OCD Awareness Week in October 2011:

Hello. My name’s Karen Robinson. Ashley asked if I could write something about stigma and OCD. So I have put together a few thoughts, drawing on my personal experience of OCD and seeking help.

My OCD came on suddenly and acutely when I was 18, and within months was hugely disabling, but I didn’t go to my GP until I was 42. My main reason for not seeking help was my intense fear of the stigma which I thought I would experience if I sought treatment. I put huge efforts into keeping my OCD secret, or as hidden as possible. I only told a few people I was very close to. But even then, I made efforts to shield them from the depths and severity of it, the terror. By the time I sought help, my OCD had severely affected the course and quality of my life.

After seeking help I received specialist cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for my OCD, and related problems. Over a period of years the CBT proved completely life-changing. I would never have believed that my life could be so dramatically different. It’s not possible to adequately express the joy and thankfulness I felt, and still feel. Years that I would have spent continuously washing, cleaning and checking, were now my own, to do whatever I liked with! Partly because the CBT was so incredibly effective, I also felt intense regret that I hadn’t sought help earlier.

So what was this fear of stigma, that was so powerful that it stopped me seeking help?

It was the fear, for example, that when I went to the GP, and told him or her about my OCD, a flicker, even the barest flicker, of disdain would go across their face. Maybe hastily concealed and fleeting, the flicker would nevertheless add to their power, and reduce mine.

The fear that when I next saw the doctor, maybe for a physical health problem, the way they treated me, either as a person, or in terms of medical treatment, would be negatively affected by their now (even only in the back of their minds) classifying me as a ‘mental health patient’.

The fear of having a mental health record for the rest of my life … and the effect I thought that would have on my studies, my career. The irreversibility. Once it’s there, official, even if I completely recover, it will always be there. And people I don’t necessarily know, or haven’t yet come to trust – medical staff, doctors, receptionists, occupational health staff when I apply for a job, travel insurance staff when I want to go on holiday – will make judgements about me on the basis of that record.

The fear that if I sought help I would have to share the very intimate and frightening experience of having OCD, with a therapist, regardless of whether I felt comfortable with them, or felt understood and respected.

The fear that my line manager and work colleagues might treat me a little differently, if they knew. Maybe only subtly. A slight wariness, awkwardness, unease. An extra friendliness. Treating me carefully. Looking after me. Making allowances.

Once it was official, I felt I’d be in a different camp, forever. A camp with, in the main, no obvious external marking, and yet one that was very clearly demarcated in the minds of those inside it and outside.

Much of my fear of stigma, and fear of the mental health system, was not OCD-specific. I knew people who had experienced depression, eating disorders, trauma and psychosis. Many of the people I knew had eventually accessed mental health services, although not always voluntarily, but I only knew one person who’d had a positive experience.

One thing with OCD is that you can, at a big cost and with massive effort, keep huge swathes of it secret. Perhaps particularly if you live alone. Only you know the intensity of the intrusive thoughts, the fear they generate, their relentlessness, and how apparently ‘mad’ they are. ‘Mad’ in the sense that you know perfectly well that most people would not see the risk in the way you’re seeing it. I knew with huge clarity that my feeling, and terror, that I still had semen on my hands weeks and months after I had last seen my boyfriend, and moreover that that semen could make other women pregnant if they touched something I had touched, was not ‘normal’. The fear was so strong that it was making me avoid using shared toilets, and eventually led to me wetting the bed.

I had no doubts that I was unwell mentally, and needed help. But each time I weighed up the potential risks and benefits of seeking help from the mental health system, with all its associated stigmatisation, I concluded that it was better for me to struggle on alone. I re-considered, and re-evaluated that decision many times over the subsequent decades, but each time I eventually, painfully, came to the same decision.

I eventually sought help, not because I felt the risk of stigmatisation had got any less, but because I had very sustained and loving support (but no pressure) from my partner, and a counsellor from a voluntary organisation. And so eventually I felt able to face the mental health system. The first two years of seeking help were grim …. far worse than the decades struggling with OCD on my own. However, when I began having CBT with an NHS therapist who was highly experienced in OCD and treated me as a completely equal human being, the remarkable changes began to happen.

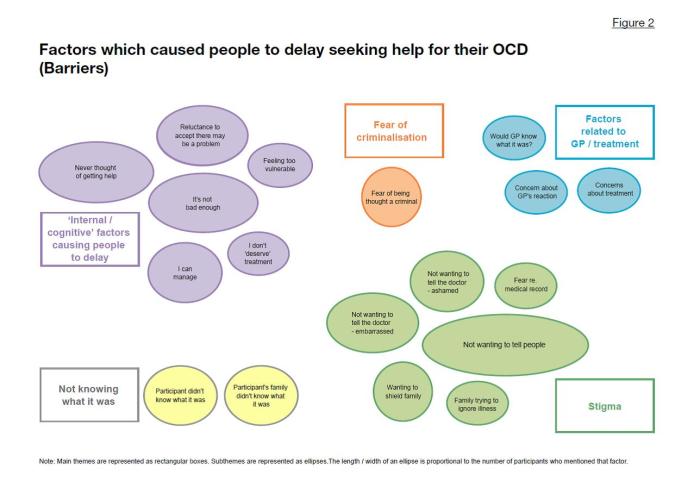

Reflecting on my experiences of seeking help I decided to train as a mental health researcher. Some members of OCD-UK may remember kindly participating in a research project I conducted a few years ago looking at the factors which encourage people to seek help for their OCD and the barriers to seeking treatment. Many participants described stigma-related factors which acted as barriers to their seeking help. I am now working on a larger-scale research project, drawing on the themes found in the initial study, and trying to find out whether these themes are also true for a much larger number of people with OCD.

So, to what extent did my long-held fears of stigma turn out to be true when I eventually did seek treatment? Well, my experience has been very mixed.

I still find nearly all mental health buildings scary, institutionalised and stigmatising. I have met a few mental health professionals who are warm, natural, respectful and completely non-stigmatising. Indeed, they are actively acting against stigma in the way they personally behave, and in the wider world. I think more mental health professionals would be like that if their training gave them the confidence to be, and if their subsequent experience of mental health practice did not de-sensitise and harden them. Sadly, when I think about the people I have met who have been the most stigmatising, mental health professionals feature prominently.

Since seeking help I have been much more open with people about my history of OCD, including with potential or actual employers. They have responded in a range of ways, from very positive, to pleasant but quite awkward, to very negative in quite a subtle way. Their reactions have probably reflected their levels of awareness and at-easeness about mental health, and the extent to which they see people with mental illness as equal to them, or ‘other’.

In the wider world, in general people have been much less stigmatising than I anticipated. It is not uncommon for people to tell me about a mental health problem that they have experienced or someone they know has experienced, after I have told them about my OCD.

It is a huge relief not to have to put all that energy into hiding a part of myself. It makes me feel infinitely more confident in the world not living in dread that someone might find out this stigmatising thing about me.

However, depending partly on my level of confidence on the day, and whether the other person is in a potentially powerful position in relation to me, I am still selective about who I tell. For example, I found myself deleting my e-mail signature which says ‘Researcher with personal experience of OCD and CBT’ when I wrote to a mortgage provider recently, and didn’t explain why I was so interested in doing research on OCD when I was in conversation with a potential landlady.

So, in some situations stigma has been as bad, or worse, than I feared, in others not as bad, and in some not present at all. However, the effect of my eventual treatment was beyond my wildest dreams. And I have met other people who have been hugely helped by specialist CBT for OCD. So I would urge anyone hesitating about seeking treatment, maybe because of stigma-related concerns, to summon all the support they possibly can and go for it. And keep going, and keep going, until they find someone who is skilled at CBT for OCD and who they feel totally comfortable working with.

Thank you to OCD-UK for all the work you do, in public, and in hundreds of private conversations, to support people with OCD, raise awareness of the condition, and work towards the availability of prompt, good-quality treatment for everyone who needs it.

Karen Robinson

9 October 2011